Artificial Intelligence

Artificially Intelligent Image World

Andreas Müller-Pohle

[German | French | Polish | Slovenian | Chinese]

The greatest transformation of our time is that from natural to artificial intelligence, an epochal process at the center of which is a medium as familiar as it is trustworthy: photography.

It was a stark warning with which the Center for AI Safety, a nonprofit research institution based in San Francisco, startled the public: The danger of “extinction from artificial intelligence” should be given the same global priority as pandemics or nuclear war. Hundreds of renowned experts signed the declaration, including Geoffrey Hinton, one of the pioneers of deep learning, who had recently ended his long-standing collaboration with Google in order to be able to speak freely about the existential dangers of artificial intelligence. That was in May 2023.

Admonishers and Appeasers

Hinton is one of the most prominent voices warning of the threats posed by a technology that comes in the guise of harmless text and image creations – and yet has the potential to turn upside down just about everything that makes up our Western value system. It is not even necessary to look into the distant future, it is enough to consider the dynamics of the present. And that is confusing enough. Here, the admonishers are confronted by the appeasers, who see it all as hype, a passing wave, or even just a burp of the digital revolution that happened more than three decades ago and should no longer frighten us.

Why should we fear it? Artificial intelligence is already present in almost every device, in every sophisticated software application, and it is hard to imagine any technologically relevant area of society without it. Whether in medical diagnostics, language processing, or industrial robotics, it helps us in our everyday and professional lives – but it is camouflaged, like a virus that spreads insidiously and does not rest until it has complete control of the infected body.

At the end of 2022, a worldwide sensation was caused by the launch of ChatGPT, a program that can generate language from myriads of existing training data – not in the sense of semantic understanding of any kind, but purely formally and statistically along learned syntactic structures. Since then, the number of artificially intelligent texts has mushroomed, with email and business applications being the least interesting. Novels and poems are already being written. Yes, even plays.

Months earlier, the world of images had been shaken by intelligent generators such as DALL-E 2, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion, which can generate images from text input, so-called prompts. And video and sound generators are also on their way to conquer the universe of the senses – dozens of programs and tools, already amazing and disturbing, yet only in the early stages of their development.

The fact that artificial intelligence, whose history dates back to the middle of the last century, is only now coming at us with a vengeance has to do with three main factors: the availability of gigantic amounts of data (big data) as a product of social media, online commerce, and other areas; the rapid increase in hardware performance made possible by new graphics processors and storage technologies; and advances in machine learning, especially deep learning.

Super Black Box

We owe the current exponential development of artificial intelligence first and foremost to advances in self-learning systems – systems that can constantly improve their performance based on their experience and thus accelerate themselves, with incalculable consequences for the controllability of the processes set in motion.

The almost limitless complexity of neural networks and the escalating pace of research that drives them make artificial intelligence a black box of a new quality. Even its prototype, the photographic apparatus, was a camera obscura that could only be understood with technological knowledge. The computer, the next stage, obscured its inner workings in the shadow of codes, ruled solely by its programmers, that new class of literati and scribes. And artificial intelligence? It works, but even its creators no longer fully understand how or why: a super black box.

In many areas, this is irrelevant; in others, such as autonomous driving, it is existential. Decisions about life and death, made in the darkness of a black box – the idea rightly fills us with dread. And this is also the ethical crux of artificial intelligence: Without the penetration of its processes, without its plannability and traceability, effective rules and laws for our protection are unthinkable.

Such rules and laws are being hotly debated in photography, especially in applied photography, and are paradigmatic for a multitude of professions whose ground is being pulled out from under them by the new potentials of artificial intelligence. In the crosshairs is a profession whose expertise, the production of camera images, will foreseeably no longer be needed in many commercial applications, and whose capital, the image and author rights, will melt away in the blink of an eye.

Simulated Photography

Two worlds of images confront each other: on the one hand, photography by means of a camera, on the other, image generation by means of a computer; here the image of light, there the image of data. They are two of the most unequal siblings. For those data that are now being devoured and digested by the algorithms of artificial intelligence are the estimated more than twelve trillion photographs (plus all other types of images) that have accumulated in the memory of history and are available there as a sedimented mass of data.

The new, artificially intelligent image is so different that we can no longer call it “photography.” The photograph as we know it, whether analog or digital, whether taken with a camera or a smartphone, is the product of a captured light event, an optical imprint of the external world based on the sensory perception of a human actor and his or her direct, primary, authentic relationship to it. Photographs are two-dimensional slices of a four-dimensional space-time; they are per se analytical.

In contrast, the artificially intelligent image is the product of neural algorithms and statistically processed data. Its relationship to the external world is indirect, secondary, derivative. It can simulate but not embody photography: an image based on the mental input from a human actor and his or her staged relationship to the world. Artificially intelligent images are two-dimensional montages of data from other two-dimensional surfaces; they are per se synthetic.

A new vocabulary has not yet been established. Adding attributes such as intelligent, generated, or algorithmic to photography leads to a dead end, because even a correct attribute cannot save a false noun. “Synthography” and “promptography” have been suggested as alternatives; let us wait and see which one will prevail in the end.

The transition from the light image to the data image is accompanied by the abolition of the author – once again, and this time for good. For if every new image is a composite of already existing images, then every one of its creators becomes a potential author – even if only infinitesimally, even if homeopathically diluted like a drop of blood in the ocean.

Truth and Probability

The visual world of artificial intelligence marks a qualitatively new stage of digitization. From the very beginning of this process in the 1990s, it was clear that photography would play a key role.

The most far-reaching social consequence is the decline of truth, the bastion that photography once built eye to eye and hand in hand with the natural sciences. It was photography that, for more than a century and a half, conditioned us to trust the eye. All our skepticism, all our theoretical insights into the artificial, constructed, staged character of the photographic image have not been able to destroy the idea that the camera is a truth machine that provides us with reliable and trustworthy documents and evidence.

This naïve belief in truth was shattered with the digitization of photography. The analog threads that had once connected photography to the world out there were chopped up into bits and could now be reassembled, computed, at will. Truth was no longer an automatic, technically guaranteed feature of the image, but became a question of journalistic integrity – of certain media, agencies, and individuals with impeccable reputations.

From then on, a new social calculation was required, one that replaced truth with probability, and that today, in the face of artificial intelligence, confronts us with entirely new challenges. For once photography as we know it is eroded, once it is marginalized and pulverized, once our image of the world is distorted by more and more invented, fictitious, mendacious constructs, even liberal civilization comes under threat. Its cohesion is based on a double consensus: the credibility of images and the credibility of science. When the credibility of images fails, science suffers as well, as we are experiencing with the climate crisis: Only since the images of droughts, floods, and melting glaciers have come into existence, does it exist at all.

Artificially intelligent images are – to repeat – not photographs. They can pretend to be photographs, just as photographs once pretended to be reality. This is a qualitative leap that not only justifies but requires us to speak of something revolutionarily new.

Aesthetic and Political Kitsch

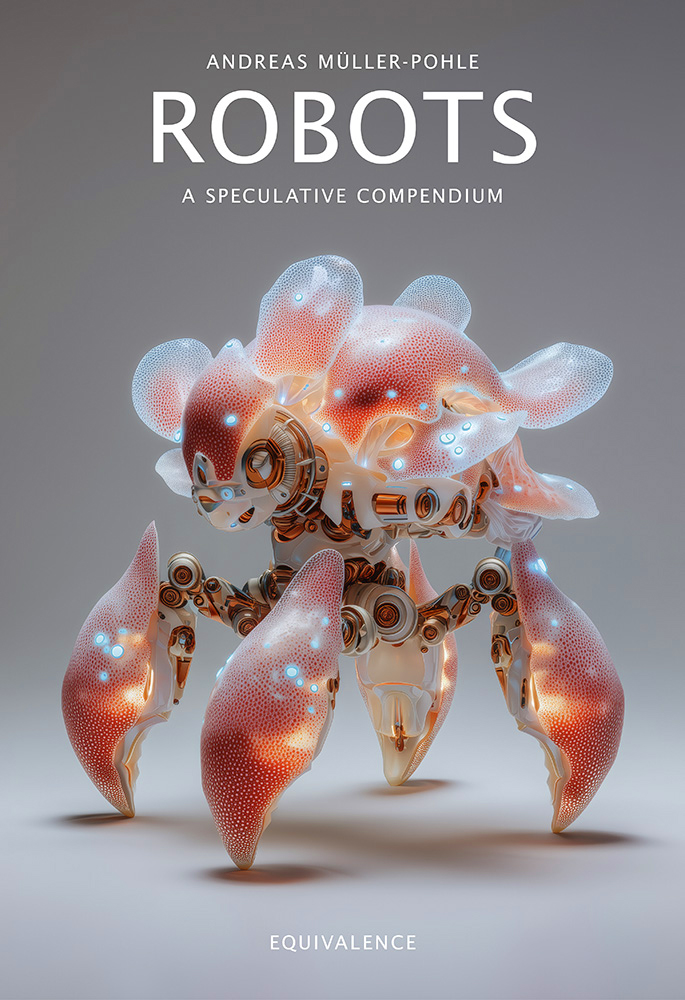

A look into the sites and channels of artificially intelligent images makes one shudder at times. It hisses and bubbles like in a witch’s kitchen. Creepy monster figures next to athletic super-bodies, horses running through living rooms, dogs as big as elephants . . . an endless stream of kitsch and nonsense, perfectly styled and yet so uniform and redundant that one wonders where exactly the much-vaunted expansion of photographic creativity is to be found. At the moment, you have to look for it like a needle in a haystack. For the kitschification of the image sphere results almost inevitably from the amalgamated nature of artificial intelligence, which – this seems to be its paradox – produces above all artificial stupidity with all its empty and used images.

The counterpart to aesthetic kitsch is political kitsch, which gelatinizes and reshapes social discourse, to be found in the ideological bunkers, the bubbles and echo chambers in which hallucinated, alternative, freely invented realities circulate. It may seem unrelated at first glance, but both forms of kitsch have a common – if not sole – cause: the decay of certainty and truth in their original and elementary sense as a correspondence between statement and reality, as established theoretically abstract by the sciences and sensually concrete by the technical image media.

Knowledge Regression

Aesthetic and political kitsch – that sounds harmless, and yet it is the swamp from which even the most liberal and democratic societies are threatened. A society without a compass, without an anchor, is easily lost. “Muddying the water” is the term for the strategy of undermining certainties, sowing doubt, and making lies acceptable. Artificially intelligent images that pretend to be photographs are the instrument of choice for this. For they are ideally suited to exploit and abuse our traditional trust in photography – and even more so in the moving image. And we are, it must be emphasized, only at the beginning of this process. The still prevailing imperfection of artificial images, be it the Pope in a down coat or Trump in a scuffle with policemen, will soon be a thing of the past. The great pictorial horror is yet to come.

A peculiar nostalgia is already spreading, a longing for the happy days when we believed we could trust the evidential value of the photograph. And indeed, for all the fascination with the artificial new intelligence, there is one thing worth defending: the authentic camera image, created in the light of reality. Technical approaches to this already exist, such as the Content Authenticity Initiative, which aims to provide photos, videos, and audio recordings with tamper-proof metadata about their origin and processing.

Yet it seems that the debate about photography and its relationship to reality, so fiercely fought over the past few decades, has been increasingly lost from view. Its ontological status, until recently classified as subjective and programmed, appears to have shifted back into a zone of seemingly objective authenticity in the face of the artificially intelligent image. Data can lie, light cannot? That would be a fatal conclusion. Let us be immune to such recursions, which throw us back into the debates of yesterday and the day before.

Artistic Strategies

The aesthetic history of photography can be seen as a reflection of its technological development: Technical innovations have always opened up new artistic creative spaces, and the more significant the innovation, the more powerful the subsequent creative expansion. It is still too early to sketch out an adequate scenario for the immense upheavals of artificial intelligence, but some approaches and strategies can be named for how artists are meeting the challenge today.

Above all, they resist the temptation to use it as a mere toy, to play naïvely with it instead of against it. To let it spew its kitsch unfiltered. Instead, they develop narratives and concepts in which reflection and critique resonate. Their perspective is a theoretical one, a meta-view.

The most promising approaches we see here often bear a striking resemblance to those of conceptual and appropriation art. For today’s digital avant-garde, everything is up for grabs again: history, the media, science and politics, philosophy and art. No dogma or knowledge, no matter how ironclad, remains untouched by them.

But the new artificial intelligence strategies will not only rewrite the past and illuminate the present, they will above all cut a swath into the future, providing forecasts, models, symbols for tomorrow’s life and survival. They will be integrated strategies in which the circles of art intersect with those of the natural sciences and humanities, architecture and urban planning,

ecology and many other fields. A cross-media art, an art of interfaces, where the still image becomes a function of the moving one and an element of the expanded immersive space.

It will be up to us to counter the threatening potential of artificial intelligence and instead develop it into an instrument of cognition and sensibility. The intelligence we need for this is and will remain our own. For the artificially intelligent images of the future will only make sense if they remain human images.

Berlin, October 2023

© Andreas Müller-Pohle. First published in European Photography, Berlin, no. 114, vol. 44, winter 2023/2024