The European Photography List of Forty Books

Twenty photobook connoisseurs were invited to nominate their favorites from four decades – one from the years 1980 to 1999 and another from 2000 to today. An imaginary library, reflecting the fascinating cosmos of the photobook. First published in European Photography’s 40th Anniversary Issue #105 (2019)

Jens Friis Editor and publisher of Katalog magazine, Kerteminde, Denmark

Robert Adams: Beauty in Photography – Essays in Defense of Traditional Values. I discovered this collection of essays when I settled in New York for a short while after working for four years in a London gallery. At that moment in time, I was pretty fed up with photographs being seen as collectors’ items and a commodity. Robert Adams’ writing about art and photography simply put me back on track as a passionate lover of photography as art. Adams is himself a formidable artist – so he knows what he is talking about – as well as an eloquent writer with great insight. In nine chapters, he investigates subjects such as “Truth and Landscape,” “Beauty in Photography,” and “Civilizing Criticism” in plain words. His humble and humane approach continues to be an inspiration to me. This is the book that I read again and again.

Pentti Sammallahti: Here Far Away. Pentti Sammallahti is a master photographer, printer, and bookmaker. I experienced his childlike enthusiasm for excellent printing firsthand when he came directly from the printers to a meeting with me. It was contagious, to say the least. Over the years, he has produced many beautiful books – too many to mention. Each stands out as a unique pearl. His images are infused with an understated humor and an innocent wonder of the beautiful world, as if seen for the first time. This particular book collects many of his best images in one large volume, superbly printed in collaboration with six different European publishers. That the book is graced with a preface by my former colleague and director of the Museet for Fotokunst, Finn Thrane, further adds to its appeal and attraction. A true gem.

Hiromi Nakamura Freelance curator, Tokyo

Shin’ya Fujiwara: Mémento–Mori. In the 1980s, on the eve of the bubble economy in Japan, people developed an excessive lifestyle of superficial joy and amusement that everyone believed would last forever. At that extraordinary moment, this book attacked our “bubble” brain and opened our eyes: Memento mori, remember you must die. The seventy-four color images in this paperback-sized book confront us, with short comments, with our infinite lies about death – a picture of a stray dog, for example, greedily looking for the corpse of a man discarded in a wasteland, accompanied by his words “We’re so free to be bitten by a stray dog.” After the bubble age was over, the book remained an incredible long-seller with hitherto twenty-plus additional editions in Japan.

Maija Tammi: White Rabbit Fever. This book examines the representation of disease in art photography and shows new ways of dealing with the phenomenon of illness. Published as a dissertation, it includes Maija Tammi’s own works, as well as artistic research conversations with critics, scholars, and other stakeholders. Her starting point is the private sphere, but the theme expands to a universal questioning, from a micro-cell level to a black hole of a big bang.

Jeanne Mercier Curator and co-editor of Afriqueinvisu.org, Paris

Roger Ballen: Platteland. “Platteland” is the literal translation into Afrikaans of the term “flatlands,” which refers to the South African countryside with its open, monotonous, and at times brutal landscape. But the word is more than just a geographical term – and that’s what we feel in the work of Roger Ballen, an American photographer who has been photographing South Africa for more than forty years. In this book, Ballen has photographed a world that lived under the mantle of white supremacy. Black-and-white portraits reveal a population strangled by poverty. Platteland shows the inevitable failure of a regime that served only the welfare of the privileged white minority of South Africa. Published at the time of the election of Nelson Mandela and the end of apartheid, this book is one of the milestones that made the work of Roger Ballen famous.

Deborah Willis: Reflections in Black. A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present. The first comprehensive history of black photographers, a groundbreaking pictorial collection of African-American life. If this book is essential, it is because it tells a common heritage, a collective story. Every US library and family should have it. There are 600 images showing a glimpse of black life, from slavery to large migrations, from portraits of several generations to middle-class families in the 1990s.

He Yining Writer and curator, Tianjin, China

Victor Burgin (ed.): Thinking Photography. Thinking Photography is a collection of essays by such renowned writers as Walter Benjamin, Umberto Eco, and Burgin himself. The book not only affected the theoretical reflection on the history of photography, but also broadened the reader’s horizon on the research pattern of visual culture. It has exerted a great influence on my understanding of the history of photographic media and its position in visual culture.

Chen Zhe: Bees & The Bearable. Combining Chen Zhe’s series The Bearable (2007–10) and Bees (2010–12), this book not only contains images that document the artist’s five-year history of self-injury and stories of others like her, but also includes a collection of quotes, diary entries, online chat histories, and letters exchanged over a two-year period. In this book, image, text, and design form a perfect unity.

Damian Zimmermann Curator, critic, and blogger, Cologne

Larry Sultan: Pictures from Home. For me, it’s a masterpiece. This is certainly due to my very personal interest in the themes of the book: family, parents, origins, and memories, as well as the melancholy and limitations of the medium of photography and the attempt to work against these. Ultimately, it’s about the desperate attempts of human existence not to forget. And not to be forgotten.

Andrew Phelps: Cubic Feet⁄Sec. 34 Years in the Grand Canyon. On the surface, Cubic Feet⁄Sec is a journey through space. In fact, however, it is a journey through time, since the photos are from nine trips Andrew Phelps and his father Brent took on the Colorado River between 1979 and 2013. When they emerge from the river at the end of the book, they are thirty-four years older. But it’s also a book about failure: “I could never help feeling that photography was never going to do what I wanted it to do. This failure, of course, is not photography’s, but mine and my lack of understanding what it can never do.”

Sebastian Arthur Hau Book expert for Catawiki and Director of Polycopies and Cosmos, Paris

William Eggleston: The Democratic Forest. A sequence of images that is in my head, just like a movie that I have seen many times. Perhaps this book does not make the bold statement that Eggleston is a genius as strongly as his Guide, published more than ten years earlier, but it is my favorite. First comes the sensuous experience – of heat, space, air, wind, movement. Of liberty and formal constraint. And an edit that slowly winds through a possible story, even if it were only of a voyage, moving slowly into larger subjects (the corner of the house where Kennedy was shot), taking you by your hand like a storyteller. Of course, these images do not convey their meaning through words, but rather by visual clues, justifying his daring statement “I am at war with the obvious.” The book strives for modesty, better achieved by Faulkner’s Mississippi, published a year later, but is perhaps more influential because of its texture between visual and literal readings, not far away from how a movie feels.

Batia Suter: Parallel Encyclopedia. One might claim that this publication is not particularly well-liked. But after many years of expanding the world of the photobook, with the incredible rise of small, independent and self-publishers, the Encyclopedia seems to me the most necessary book around. As I open it now, the path leading to clarity through the jungle of images, allusions, and knowledge again appears cut with a clear eye and stable hand, and without diminishing or damaging the material. There are no aberrations, tricks, or jokes that other compilers and editors of found material work with; the images in their overwhelming amount are printed just adequately enough to be seen and understood, and yet the author and publishers disappear behind the work, the book does not feel impersonal at all. It appears contemporary in that it derives knowledge from the compiled material and traditional in its love and respect for that material. This a very enjoyable book to pick up again and browse and study.

Miwa Susuda Photobook consultant and publisher at Session Press, New York

Joji Hashiguchi: Shisen (“The Look”). Portraying people who live on the edges of society has been a popular theme in the history of photography. Japanese photographers such as Nobuyoshi Araki, Katsumi Watanabe, and Seiji Kurata were also passionate about it and published many lively and powerful works about yakuza and prostitutes in Tokyo. Among all the masters, I admire Joji Hashiguchi’s work the most, because he has dedicated his entire life to portrait photography and has documented a vast array of people not only in Japan but all over the world. Shisen (“The Look”) is the first body of Hashiguchi’s work on young rebels in Tokyo, and it marks a change in direction he pursued for the following forty-plus years of his long career. His dedication to photography is truly honorable and significant to the following generation of photographers.

Lieko Shiga: Rasen Kaigan. The arrival of Lieko Shiga on the photography scene was quite a sensation in the history of Japanese photography. Shiga cleverly evolves and expands her conceptual ideas, starting from pure straight photography and unfolding the potential of documentary photography with her unique visual language, which often involves physical manipulations of analog images. Her work is based on detailed investigations of a variety of subjects, never looking too contrived or limited, but rather welcoming and free. Shiga is definitely one of the most exciting talents among the current generation of photographers, and her book is indisputably recommended.

John Fleetwood Curator, educator, and Director of Photo:, Johannesburg

David Goldblatt: In Boksburg. I only got to really look at the book when I was in my early twenties, while I was still a photography student. It was about a decade after the book was published. In South Africa at the time, photography was very much dealing with the urgency of resistance against apartheid. Images of protest and violence were everywhere, and yet the propaganda and social machine of apartheid maintained a kind of domestic bliss for the privileged, white South Africans. The undercurrent of that moment was that things would change. The images in In Boksburg were complicated, as they partly spoke to my own identity and sense of belonging; at the same time, they resonated with my rejection of parts of this identity. Goldblatt passed away in 2018, so this nomination is also a tribute to him.

Dana Lixenberg: Imperial Courts 1993–2015. There are so many good books, so for now, this is just one of them. It’s about the simplicity of portraiture, which is why I am so drawn to this book. In the sustained engagement of more than two decades, Dana Lixenberg’s position remains so constant. The portraits do not perform beyond the original interaction – they remain true to the moment of interaction between the photographer and the person photographed. For me this is remarkable. Yet we can see how photography changes, how people present themselves, how photography is a language spoken by many.

Markéta Kinterová Director of the Fotograf gallery and magazine, Prague

Lukáš Jasanský⁄Martin Polák: Pragensie 1985–1990. This book perfectly represents what was symptomatic of the morbid spirit of the late 1980s in Prague. Lukáš Jasanský and Martin Polák, at that time students at FAMU, were able to capture it through a technically precise approach, commenting on the banality of situations, as well as on the limitation of reportage photography itself. With this approach, they had anticipated what had more or less become the core of their visual morphology. The book was published as a catalog for their exhibition eight years later, and it had a very strong impact on the Czech art scene, as it was Jasanský’s and Polák’s first larger-scale publication.

Ivars Gravlejs: Early Works. Publishing work done as an adolescent is a brave gesture, even if it is later considered a great piece of art. Ivars Gravlejs started taking pictures at the age of eleven. This offered him a way out of the humiliating experience with his teachers: “The only way to survive school was to do something creative – to take pictures and make movies.” He captured his daily life with the camera and often processed his images to absurd montages. Early Works is a rebellious, fresh, and hilarious response to the crisis of puberty, with

all its challenges to test the limits of society.

Matthias Harder Chief Curator at the Helmut Newton Foundation, Berlin

Herbert List: Hellas. I fell in love with this perfectly printed and subtly designed book – and List’s photography in general – when it came out. I later wrote my doctoral thesis on Herbert List’s temple photographs taken in Greece (in juxtaposition with those by Walter Hege) and co-edited List’s monographic book. List developed his pure and timeless photographic style in Greece in the 1930s after he left Nazi Germany.

Masao Yamamoto: É. The layout of this book is outstanding with its huge format and almost empty pages. The photographs, mostly calm, sensitive still life motifs, landscapes, and nudes, are reproduced in their original sizes of just a few centimeters. They are placed precisely on the double-pages, and the thin paper of the book reveals the reproductions of the photographs on the previous pages as small shadows, like fading visual memories. Masao Yamamoto is a poet with a camera.

Daniel Boetker-Smith Director of the Asia-Pacific Photobook Archive, Melbourne

Mao Ishikawa: Atsuki Hibi in Kyampu Hansen (“Hot Days in Camp Hansen”). There is nothing else quite like this book. This is proud Okinawan photographer Mao Ishikawa’s documentation of her friends and their African-American GI boyfriends⁄lovers during the mid-1970s. Photographed in segregated bars in Okinawa over a number of years, this is a great example of a complex and richly connected story told simply and honestly. This book is majestic in its specificity and is the precursor for many similar books that have followed.

Dayanita Singh: Sent a Letter. Singh has changed the face of photobook publishing over the last thirty years and rarely gets enough credit. Her books are the perfect mix between experience, narrative, and beautifully intoxicating photographs. Sent a Letter is comprised of a series of small leporello books, each made with a certain person in mind, and documents a time shared between subject and photographer. A timeless masterpiece.

Thyago Nogueira Head of the Contemporary Photography Department and Editor of Zum magazine at the Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo

Miguel Rio Branco: Silent Book. The publication of Silent Book was a punch in the stomach, with its intense color-saturated photographs of bodies, animals, churches, and orifices, precisely cropped and breathlessly sequenced. Despite its small size, it screamed at the paradoxes of attraction and repulsion, machismo and violence, religiousness and eroticism, guilt and redemption which permeates Brazilian society.

Rosângela Rennó: A01 [cod.19.1.1.43] — A27 [s|cod.23]. In this austere book, Rennó documents what was left from a theft in Rio de Janeiro’s General Archive, when historical photographs mysteriously disappeared from their boxes. The layout emulates the mutilation of the albums and images, while the book in itself, printed in few copies and distributed to national archives as a memento of the theft, became a coveted object that ironically commented on the collateral damage caused by the art market and the world of collecting.

Liz Wells Writer, curator, and Professor of Photographic Culture at the University of Plymouth, United Kingdom

Verdi Yahooda: Principle of Uncertainty. This is the first photobook that I felt absolutely compelled to buy. Yahooda was in the vanguard of the recent interest in artist photobooks. The theme is memory and loss, the locations referenced seem to be somewhere in the Middle East. Soft gray-scale images lightly float on the pages, lending a melancholic mood. The layout is not uniform. As we journey across the pages, she juxtaposes impressions of desert lands and interior spaces. Flowers, a plant, and domestic objects crowd a table and shelving, stilled through photography and embalmed in memory. A photographic slice of the face and hat of a younger woman appears as a vertical strip across a panoramic arid landscape, the picture repeated twice with a slightly closer-up variation on the second occasion. Needless to say, words do not do justice to the visual rhetoric that speaks to the interrelation of photography and memory. This is not a well-known photobook. Its fluid positioning of pictures and the complete lack of captions or anchoring text render it unusually haunting.

Edward Burtynsky: Oil. I chose this book because of the contemporary significance of the theme addressed. It demonstrates the power of photography to influence attitudes, while at the same time testifying to the persistence of the photographer in reflecting on the globalization of industrial activities, how this is manifested visually, as well as on the implications of this extraordinary transnational set of economic relations. It is not an experimental book, but it is one (among several of his publications) that powerfully contributes to reflections on the implications of capitalism in the era of the Anthropocene. The images are high-quality in terms of aesthetics, to the extent that the paradoxical beauty of many of the single images risks distracting from the underlying issues addressed. But brought together in the form of a book, the imagery comes together to form a clear and worrying message; as such, it has contributed to emphasizing the urgency of climate change action.

Brad Feuerhelm Artist, curator, and editor at Americansuburbx.com, London

Hans Danuser: In Vivo. Danuser’s In Vivo is one of the coldest books that I have come across. There are glimpses of bodies, anatomical tools, and stainless-steel surfaces. The overall feeling is minimal, with strange abstractions of clinical apparatus running throughout. It feels as though I have entered a cryogenic lab, and my waking life has been stored elsewhere on a hard drive. It is not a common book, and I do not know how applicable it is for most, but Danuser’s attention to minimalism and his uncompromising look at death gives the book a nod toward the universal. The oversized physical dimensions of the book pull the reader into the theater of the macabre.

Michael Schmidt: Lebensmittel. First, it is important to say that I think the theme of the book, although ostensibly about food production (the reason he won the Prix Pictet in 2013), is apparent. What is more prescient is that Schmidt is, in my mind, speaking about the condition of being a human in mid-life. There is a strange apathy that involves looking at food and contemplating how much has gone through your body by mid-life. It counters life with sustenance, and I think it is more of a rumination about Schmidt himself than the production of food. It works on the level of metaphor, and I still find it strange that this was never discussed. Ultimately, it could be suggested that, like Bowie’s Black Star, Lebensmittel was a preface for the author’s death and a swan song of sorts.

Katrina Sluis Head of Photomedia at the Australian National University, Canberra, and Adjunct Research Curator at The Photographers’ Gallery, London

Paul Wombell (ed.): Photovideo: Photography in the Age of the Computer. A prescient and pioneering publication (and exhibition) of 1990s post-photographic culture which predates another iconic publication of the time, Photography after Photography: Memory and Representation in the Digital Age. Theorizing the photograph as a moving image or “transmission,” Photovideo traverses photography and virtual reality, surveillance, biometrics, racism, and the military-industrial-entertainment complex. Although I was only thirteen years old when Photovideo was published, it became a valuable reference for me during my studies in the late 1990s and still feels relevant today.

Silvio Lorusso⁄Sebastian Schmieg: Five Years of Captured CAPTCHAs. A monumental series of five leporello books that chronicle every CAPTCHA the artists Silvio Lorusso and Sebastian Schmieg solved over the course of five years. Spanning a total length of ninety meters, the books document the CAPTCHA’s evolution: from a “utopian” crowdsourcing experiment to digitize the world’s knowledge to a method for improving Google Street View and teaching self-driving cars to see. The books therefore attest to a moment in history when the ability to “read” a photograph and extract meaning from it remained a uniquely human attribute.

Regina Maria Anzenberger Director of the Anzenberger Agency and Gallery, Vienna

Françoise Huguier: Sublimes. The at times almost abstract pictures and vivid colors have fascinated and inspired me at a time when I still mainly painted. For me, this is the best book about fashion.

John Gossage: The Complete Berlin. In addition to the wonderful and great photographs, I love the graphic design, including the use of colors and typography by John Gossage himself. If you speak of a photobook as an art object, this is, for me, one of the most perfect works by a photographer and artist. What is more, there are also excellent texts by Gerry Badger and Thomas Weski.

Irène Attinger Head librarian at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris

Sophie Ristelhueber: Fait – Koweit 1991. According to Sophie Ristelhueber, her books “are not photo books in the sense of big illustrated books, they are artist’s books that I have often had published conventionally with traditional publishers.” Having arrived in Kuwait in October 1991, seven months after the end of the first Gulf War, she spent four weeks crisscrossing the desert. In Fait, published in the mass-market format, there are full-page photographs of the desert ravaged by battle, some of them showing close-ups at ground level, others showing aerial views. The terrain is disfigured by traces left from the zigzag pattern of the trench systems and damaged by the dozens of craters formed by missiles. Beyond its aesthetics, the quality of this book lies in its shift away from war reporting. The human consequences are neither shown nor seen, and yet they are there, implicitly. The photographer shows that the causes of suffering from war are lost in an inevitable cycle of eruption and erasure.

Anaïs Lopez: The Migrant. The Migrant tells the turbulent story of a Minah, a bird from Java that became a public enemy in Singapore. Considered as an invader, it is insulted, persecuted, and even killed. Through this story, Anaïs Lopez tackles broader themes such as the complexity of the relationship between humans and animals, the consequences of rapid urbanization, and, most importantly, the position of the unwanted stranger. Designed by Teun van der Heijden, the book uses different kinds of images in multiple ways: photographs, screen prints, reproductions of press clippings, and a cartoon by Sonny Liew, coming together to tell a story that is made up of an investigation, a testimony, and personal daydreaming. The book ends with a handmade pop-up page and includes a small booklet that tells the story of the Minah in the style of a tale. A personal, poetic, and exceptionally contemporary book.

Johan Swinnen Writer, curator, and educator, Antwerp⁄Brussels

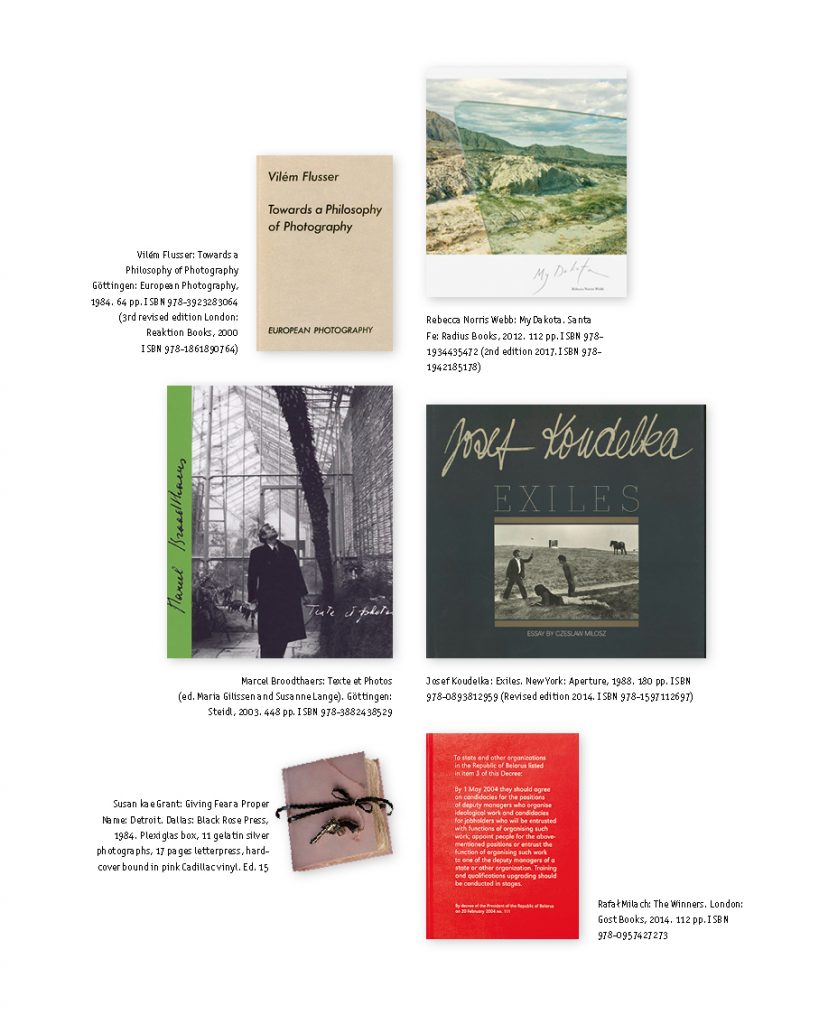

Vilém Flusser: Towards a Philosophy of Photography. Photography is an alternative to writing. In this book, first published in German in 1983, Flusser proposes a new method of analyzing photography by examining the aesthetic, scientific, and political aspects of the medium. He scrutinizes the characteristics of the traditional versus the technical image and the role of the photographer as a functionary or antagonist of the apparatus and reveals how photography can be used to explain the current cultural crisis. A revolutionary and visionary book that has a lasting impact on the theoretical discussion of photography and has been translated into twenty-five languages to date. It laid the foundation for Flusser’s recognition as a leading media theorist.

Marcel Broodthaers: Texte et Photos. This book presents, for the first time, the photographic activities of conceptual artist Marcel Broodthaers (1924–1976). The focus is on straight photography and especially on the early photojournalistic work of the 1950s, before Broodthaers went from poetry to the visual arts. Over many of his photos hangs the humanistic, slightly patronizing, and whitewashing veil that was typical of that time, with an admiration for Steichen’s Family of Man or the surrealism of Magritte and Mariën. Sometimes, his photographs place things in a different light, bearing witness to an anachronistic view

of the world that would later also characterize his art.

Mary Virginia Swanson Advisor to artists and arts organizations, author, and educator, New York City⁄Tucson, Arizona

Susan kae Grant: Giving Fear a Proper Name: Detroit. This hand-bound book of text ⁄ photographs was my introduction to the photographic artist’s book, an exciting form of traditional “artist’s books,” in which photographs are the primary visual element, often presented as sculptural or installation-based book forms. In this self-published autobiographical book, the artist shares her terrifying experience of living alone in inner-city Detroit, Michigan. The text and images illustrate a series of phobias, pairing scientifically-researched definitions with self-portraits produced as gelatin silver prints hand-applied to each page. To raise awareness of this transformative book form, Ms. Grant went on to curate Photographic Book Art in the United States, which featured book works by eighty-three artists and toured to seventeen venues between 1991 and 1995.

Rebecca Norris Webb: My Dakota. The artist takes us with her on this journey through her past and to her present within this personal photobook. The images wind between both states, depict an unsettled time in her life, and in some ways, in her homeland; yet some of the images envision a quiet, almost calming reflection. The impact of text presented in the artist’s own handwriting serves to heighten the viewer’s experience. I also greatly appreciate the list of plates at the back being presented in page-layout format which offer a score to this performance.

Adam Mazur Freelance curator, editor, and assistant professor at the University of Arts in Poznan, Poland

Josef Koudelka: Exiles. A haunting book – not only with great photographs and excellent editing, but also with an authentic contemporary message. One cannot describe the spirit of this book more emphatically than Czesław Miłosz does in his introduction: “Can we imagine a world in which the phenomenon of exile disappears because it is unnecessary? To envisage such a possibility would mean to disregard the current that seems to carry us in the opposite direction.”

Rafał Milach: The Winners. This book presents best portraits of winners – people who more or less willingly support the Belarusian regime: a bizarre August Sander-like picture of post-Soviet societies in Eastern Europe. But it also represents a photographer who is part of the system, an advocate of oppressive powers, a functionary in the sense of Vilém Flusser, who, with his camera, complies with the program of the apparatus. A best photographer who takes best pictures, produces best photobooks, wins prizes and scholarships, a photographer who best supports the system.

© 2019 European Photography, Berlin